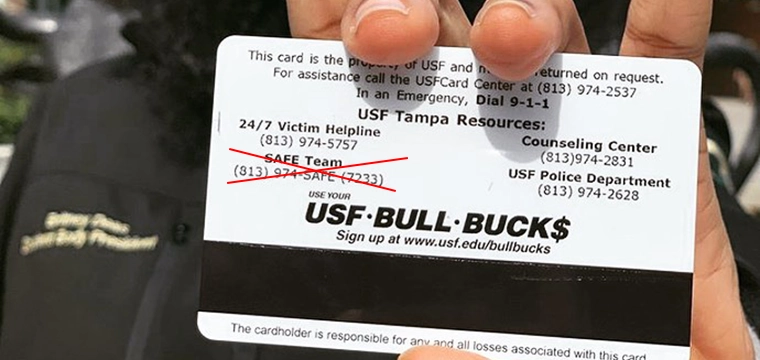

If a number changes, thousands of inaccuracies live on in purses and wallets

The back of University of South Florida’s ID card provides several phone numbers for students in crisis or seeking safety services. Many campus cards contain similar resources, but what happens when this information changes. How do you deal with incorrect contact info for essential services?

The USF card prominently lists contact numbers for the victim hotline, counseling center, campus police department, and a campus security escort service.

With the phone number change, nearly 50,000 students are left with ID cards referring them to a number that no longer exists.

When the card was redesigned in 2020, the numbers were added.

A Facebook post from the USF Student Government announced the change, saying “We are pleased to announce the release of USF’s new student ID cards! We’ve placed essential hotline numbers and other important contacts on the ID cards of all three campuses!”

According to an article in USF’s student-run newspaper, all was fine until a campus phone system upgrade forced a change to one of the numbers.

The escort service, known as SAFE Team, is operated by student government in partnership with campus police. Between 6 pm and 2 am, it provides escorts on foot or in golf carts to help students that feel unsafe walking alone.

The service was only a phone call away.

With the phone number change, however, nearly 50,000 students are left with ID cards referring them to a number that no longer exists.

This is certainly not the only time this has happened. Crisis line numbers can change and services can cease operations.

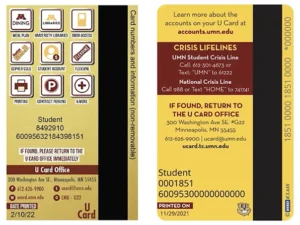

In a recent webinar, Nick Mabee, U Card Office marketing manager at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, discussed his office’s journey to add mental health resources to the back of the ID card.

The team went through at least four revisions, swapping different crisis lines in and out as they felt pressure from on-campus groups as well as pending state and federal legislation.

At one point, they had the National Suicide Prevention Hotline and the campus Crisis Line.

But before the design was finalized, Mabee says, “there was controversy about the National Suicide Prevention Hotline and their approach to privacy, so we had quite a few offices on our campus that were concerned.”

The next draft removed the national line and featured only the campus line.

From the beginning, however, a goal was to meet requirements of pending state and federal legislation that, if passed, would mandate inclusion of mental health resources on student IDs.

If we list our card’s basic services – vending, laundry, access, etc. – and one of them changes, it is not a big deal. But the same can not be said for crisis lines or essential services like USF’s SAFE Team.

This led the team to add back the national line to meet potential federal requirements and include county lines that were part of the Minnesota bill.

Old card back and new design with mental health resources

With a shortage of space on the card back and a wealth of uncertainty about the future of the legislation, the final design eliminated the county lines and featured only the national and campus crisis numbers.

While Minnesota’s U Card does not contain any incorrect numbers, Mabee’s experience shows the challenges of this process.

There will always be uncertainty when the ink hits the card.

If there is a lesson to be learned from these examples, it is that card offices and campus administrators should put careful thought into any information that is added to the ID.

This is especially true of life safety information.

If we list our card’s basic services – vending, laundry, access, etc. – and one of them changes, it is not a big deal. But the same can not be said for crisis lines or essential services like USF’s SAFE Team.

In most cases, it is not practical or realistic to reissue every student ID if a phone number changes. So all we can do is make sure any info we include is truly necessary, unlikely to change, and fully vetted.