Biometric Signature ID (BSI) has announced that its signature gesture biometric technology, BioSig-ID, has been chosen by online distance education consortium EduKan to verify student identity via the Web.

The BioSig-ID solution was chosen by EduKan as a cost-conscious solution to the growing need for authentication of students guaranteeing they are who they claim to be when online participating in post-secondary classes.

The solution requires that a user create a password consisting of three or more letters, numbers, or symbols and draw these on the computer screen. The way a person draws this password is captured and broken down into basic elements including speed, direction, length, height, width, angle, and number of strokes. These elements are compared during subsequent sign-in attempts to determine whether the user is the same person who created the profile.

The solution from BSI was chosen by EduKan officials due to its ability to keep costs low, be accepted by faculty, staff and students during the trial period and working with standard computer hardware such as a mouse to make it accessible to all students enrolled with EduKan.

Lane Community College, Eugene, Ore., is adding a key card system that will enable staff and faculty to use cards instead of keys to unlock doors and to get into specific buildings, according tot he student newspaper.

“This technology is in wide use around the world and it has many different functionalities,” said Public Safety Manager Jace Smith. “It’s going to help Lane be an active, engaged participant in the 21st century especially once we start expanding its uses.”

After Sept. 26, no staff or faculty member will be able to use metal keys on any lock on campus. The project will involve removing or changing all of the external locks.

Through the system’s software, individual cards may be coded to work during certain times for each building on campus.

Students won’t be provided key cards unless they are employed by the college.

“I think that there is a lot of promise for using this technology with students, but there has to be a commitment to the institution,” said Smith.

Read more here.

Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker has signed a new voter identification law that requires voters to show an ID with a photo when voting. Student ID cards issued by universities can pass muster as long as they contain the student’s signature and have an expiration date that falls within two years of the card’s issuance.

That may be a problem for some schools. For instance, IDs issued by the University of Wisconsin currently don’t meet that criteria and would have to be updated before students could use them to vote.

The new law requires voters to present a driver’s license, state ID, passport, military ID, naturalization papers or tribal ID in order to vote.

Opponents are expected to challenge the constitutionality of the law in court. The law takes effect next year.

Read more here.

Hamden, Conn.-based Quinnipiac University has experienced steady growth in recent years which necessitated expansion beyond its main campus. This expansion comes with the need to provide additional security for university personnel, as well as the nearly 8,000 students that live in campus residence halls.

Hamden, Conn.-based Quinnipiac University has experienced steady growth in recent years which necessitated expansion beyond its main campus. This expansion comes with the need to provide additional security for university personnel, as well as the nearly 8,000 students that live in campus residence halls.

Securing buildings located in remote off-campus locations can be a challenge for a school’s facilities department. Quinnipiac overcame this by installing WiFi-enabled locksets from Sargent Manufacturing, one of the brands of ASSA ABLOY. “Even though we expanded outside the main campus, we wanted to provide the same level of doorway security that the main campus enjoys,” said Keith Woodward, director of facilities at Quinnipiac.

Quinnipiac has a more than 30-year relationship with Sargent and ASSA ABLOY. All residence halls and academic buildings on the main campus are secured with Sargent Passport 1000 PG offline locks that operate with Quinnipiac’s Q-Card student ID program. The locking system’s Persona Campus software enables the university to set access privileges on all campus buildings and track lock usage with an audit trail feature.

Facility personnel wanted to offer this same access control to 400 doors on off-campus buildings without having to send out a technician anytime a lock required enrollment updates. A solution was available in the new SARGENT Passport 1000 P2 lockset that connects wirelessly to the school’s security network. Using an existing WiFi network, the Passport 1000 P2 connects as often or as little as specified to maintain its local list of up to 2,400 users.

The locks communicate to the host server or access control panel via an open-standard 802.11 b/g WiFi network. “This technology allowed us to implement online access control by simply tapping into our existing WiFi network,” Woodward explained. “The Sargent locks with Persona Campus software fully integrate with our campus card system and achieve cohesive, university-wide doorway security.”

With the new locks, Quinnipiac was able to simplify management of their off-campus access control so it can be used with campus IDs. In addition to opening their doors, the cards are used for meals, laundry, vending machines, copy machines, checking out books and equipment, and accessing the fitness center. There is also an off-campus program and the cards are accepted by a number of local merchants.

Privacy risk … or a fear of the biometrics boogey man?

It's a question that came up in Denver late last year when the health club chain, 24 Hour Fitness, introduced a fingerprint-based check-in system to replace its membership cards.

The move added to the debate over whether systems that use fingerprint, face and eye images for identification can leak the information and create an invasion of privacy, according to a Denver Post article.

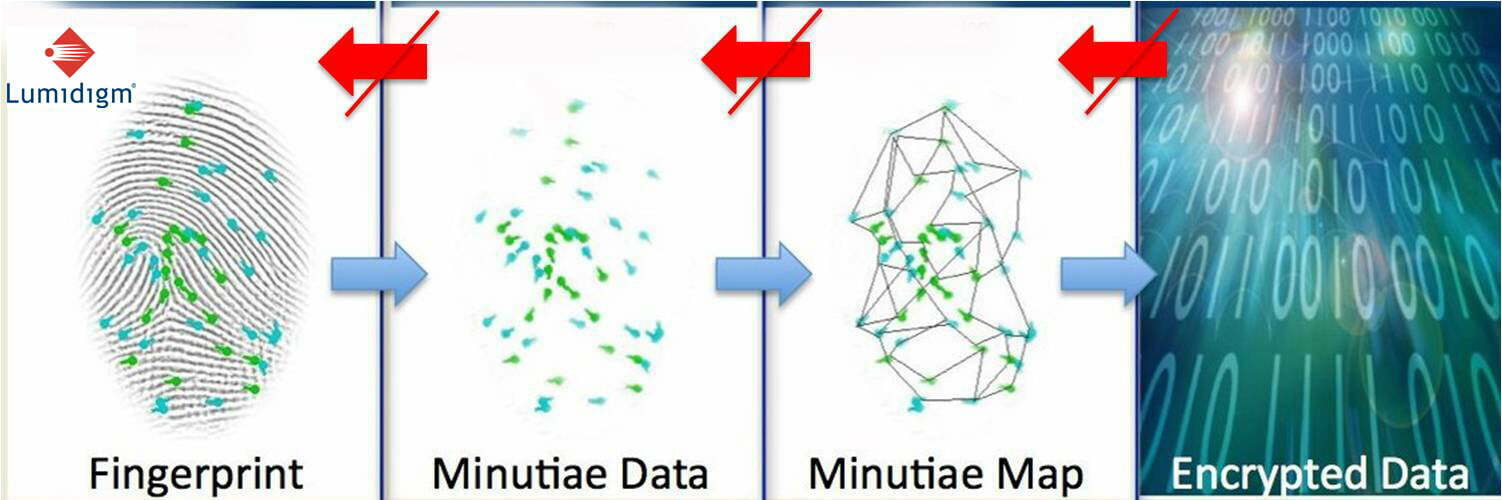

To set minds at ease, officials from 24 Hour Fitness pointed out a safeguard that biometric vendors often cite in defending their products: the system does not store actual fingerprint images but rather a numeric template that is a binary representation of specific points on the finger.

Industry experts say that when used properly, templates provide a secure method for identification that is privacy enabling. "It's not the technology, it's how you use the technology that really matters at the end of the day," says Phil Scarfo, senior vice president of sales and marketing for Lumidigm, an Albuquerque, N.M.-based biometric company specializing in fingerprint identification.

Though most biometrics systems rely solely on templates, or mathematical representations of the physical characteristic, the general public is not aware of this fact. "It is the misperception that people are storing fingerprint images in databases that creates concerns related to privacy," Scarfo says.

In every fingerprint, there are data points unique to that finger. "That constellation of points is what gets translated into this mathematical equation," says Scarfo.

The content for fingerprint, face and iris templates represents discreet visible artifacts or features, such as the corners of the mouth or shape of the eyes, says Michael Garris, supervisory computer scientist for the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in Gaithersburg, Md. "These points end up being feature points. Then you can compare the relative difference and displacement of those features between different samples," Garris says.

In its story on the 24 Hour Fitness debate, the Denver Post cites a September report by a blue-ribbon panel of the National Research Council calling biometric-identification techniques "inherently fallible."

Elaine Newton, senior adviser for identity technologies for NIST, disagrees with the statement. She says that it's more accurate to say that biometrics are "probabilistic," meaning that a biometric is not exactly the same each time it is collected. For instance, no two photographs of a person's face are precisely the same. This fact can lead to a degree of uncertainty when establishing an identity with biometrics.

Newton says that although templates on their own aren't perfect, neither are they inherently flawed. "For biometrics to be successfully fielded, they do not need to be perfect," she wrote in a 2009 report for Carnegie Mellon University. "Critical to their success is correctly designing the system."

Officials from 24 Hour Fitness said they took the extra step of encrypting the templates to provide an extra layer of privacy.

Encryption is a standard practice biometrics vendors take to guard against unauthorized viewing and reverse engineering templates, says Jim Bergen, Sarnoff Corp., a Princeton, N.J.-based technology firm that offers iris imaging products.

Whether encrypted or stored in the clear, most agree template data would be of very limited use to a hacker. "They wouldn't be able to figure out who those codes belong to anyway. They're just a bunch of ones and zeros," Bergen says.

The larger debate centers on the likelihood that an actual fingerprint, face, or iris image could be created from the limited number data points stored in a template. While some say it is possible, what that actual reverse-engineered image would look like is in question. A reverse-engineered image that could pass the biometric system's automated comparison would be far easier to create than one that would resemble a live sample that could pass human inspection.

In the case of iris templates, only the structure of the iris itself–the region between the pupil and the white part of the eye–is represented, Bergen says. That excludes eye color, size, shape and other features people typically use to recognize a person. "It is technically possible with certain kinds of iris codes to generate a sort of image from it, but it's an image that would be recognizable to an iris algorithm, not to a human being."

Still, some templates would be easier to crack than others. Proprietary templates rely on coding specific to an individual technology provider or vendor. Standard templates, however, contain information and coding common to several vendors, thus potentially making them easier to crack.

Industry experts cite several advantages to using a biometric template instead of an image. For one, there's dimensionality reduction, a reduction in the amount of space needed to store an image, Garris says. Templates make it easier to store biometric information on a smart card or other memory-restricted system.

Whereas a 1x1-inch fingerprint scan would contain about 250,000 bytes of data, a template of that scan would be smaller than 2,000 bytes. "A computer could work with those 250,000 bytes individually and try to match it for similarities or differences between other images similar in size … but that's a lot of data," Garris says. "In terms of storing and matching lots and lots of fingerprints, (with templates) you're dealing with a lot less data to have to store," he says.

Then there's the issue of speed. Being able to reliably authenticate a person's identity is significantly faster with templates. "Storing and transmitting images back and forth between a client device and a PC or back-end system is always a problem in terms of bandwidth and speed. Images are very large. Templates are very small," Scarfo says.

Another advantage is the privacy implications. Scarfo compares a biometric template to a constellation of stars. "How would you recreate an image or fingerprint from that constellation of points? You couldn't redraw the finger image. It's technically not possible."

Finally, experts say templates provide more opportunities for interoperability between systems. People may be using different devices from different vendors. By producing a standard template common to multiple vendors, a user can enroll in one system with one technology but authenticate in another system using a different technology.

While critics voice concerns that biometrics aren't well protected, proponents say fingerprint, eye and facial images were never really private to begin with. "We leave fingerprints behind on virtually everything we touch. Our face is always in public areas," Garris says. "Fingerprints and faces, they're personal things. But they're not private things."

Often, people confuse privacy with anonymity, Scarfo says. "People who want to fly on an airplane or enter a building have a right to privacy. But those granting us rights, for whatever reason, have a right to know who the heck we are," he says.

In the age of search engines and social networking, people are much more likely to give out private information–such as a social security number or an incriminating photo–that could be more damaging if it fell into the wrong hands than a fingerprint image would, Scarfo says. "There are all kinds of vulnerabilities we face these days, but I don't think biometrics is the biggest one."

You might say the concept of biometric templates dates back to the 19th century, when fingerprints were first used for identification and law enforcement purposes.

"If you have to look at two fingerprints side by side, that's not a terribly daunting task. Think about comparing that to a file filled with 1,000 fingerprints." says Michael Garris, supervisory computer scientist for the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

To streamline the process, Sir Edward Henry in the late 1800s devised the Henry Classification System for criminal investigations in British India. The system categorized different types of fingerprints by defining common finger points and other descriptive features, such as whether a print had an arch or loop pattern.

So instead of having to sort through thousands of fingerprints to find a match, a person might only have to search through the 100 that fit a particular category.

The same idea applies to biometric templates, except now it's computers instead of humans culling out matching fingerprint, iris and face characteristics.

The University of Sunderland in northeast England has chosen IronKey as its ‘de facto’ portable security provider to help protect access to data such as research papers for its network of academics around the world.

In addition to protecting its global network from using unsecured networks and internet cafes, IronKey Enterprise will also give the university’s corporate governance and IT departments an extra level of security.

After a small-scale trial with a select number of users, the university rolled out the Ironkey USB device to 130 users around the world. Initial feedback has been positive and there have been no reported problems, said a university spokesperson, who called it “a plug and play solution.”

IronKey, with offices in Sunnyvale, Calif. and Uxbridge, UK, secures data and online access for individuals, enterprises, and governments. It can protect remote workers from the threats of data loss, compromise of passwords, and computers infected by malicious software. IronKey multi-function devices connect to a computer’s USB port.

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks there were many claims about facial recognition biometrics. Some vendors claimed that if the technology had been deployed at airports, the hijackers could have been caught and the tragedy averted.

This was not one of the higher points for the technology as a number of factors show that statement to be false. First the hijackers would have had to have been known, included in the accessed database and the technology would have to work well enough to spot them in a crowd. None of these prerequisites were in place at the time.

Pilot facial recognition programs conducted shortly after 9/11 showed that the technology did not live up to hype. Almost a decade later, however, facial recognition has improved and is now showing viability as a standalone technology. Still, the idea of spotting and identifying an individual in a crowd remains science fiction.

Jonathon Phillips, an electronic engineer at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), has been working with facial recognition technology since 1993. He has been involved in the various tests NIST has performed on facial systems over the years, including the most recent Multiple Biometric Evaluation 2010. He has witnessed first hand the modality's improvements. "In 2002 the error rate was 20%, in 2006 it came down to about 1% and now it's at a .26% false reject rate," he says.

This significant improvement in accuracy has led to increasing use of the modality. Facial recognition is now being used by agencies around the globe to expedite border crossings, Philips says.

Australia has deployed smart gates that read the photo stored on an electronic passport and compare it to the individual at the gate. If the image and individual match, they can pass through customs more quickly. Other countries are piloting similar use cases for the technology.

3M has deployed systems where facial recognition is used as well, says David Starkie, international business manager at 3M. Lighting and camera quality are primary challenges with facial recognition, and depending on where the kiosks are placed special illumination may be needed. "The ideal is to match the lighting that the image was originally captured in," he says.

While image quality is important with all biometric technologies, it's particularly important with face. Anything other than what someone would typically refer to as a mug shot with proper lighting and controls may lead to a false reject or false match.

The images used in the NIST tests are mug shots: good quality, front facing still images. This is where vendors performed best, Phillips says. But when you take away the high quality images, facial systems start to fall off.

NIST has not tested how the biometric performs outside of these ideal situations. As Phillips explains, "we have not tested facial recognition any time, any place."

This makes the possibility of using facial recognition to spot possible terrorists at sporting events or airports unlikely. Harry Wechsler, a professor of computer science at George Mason University, has been working with facial recognition biometrics for more than 15 years and has published a book on the topic.

Facial recognition still needs to mature before it can be a viable modality due to the issues around lighting and positioning, Wechsler says. "What's being done with still images isn't enough," he says.

Biometric vendors need to work with video and develop systems that still function with incomplete data such as a portion of the face. They also must be able to match someone who may have a beard in one photo but be clean-shaven in another, Weshsler says.

There are opportunities to add behavioral biometrics to facial recognition to improve chances of a match, Weshsler says. "If you take a video and capture the way a person moves the head it gives you more information," he says. "We can use that data to improve performance."

As for low-quality still images, the likelihood of a match is around 65%, Wechsler says. While this may seem low, it's better than a human's ability to recognize individuals, which is at best just 50% accurate.

The best solution for facial recognition when not using high-quality images may be to use it in conjunction with a human operator, Wechsler says. "There are things a machine can do (but) one would have to think about the best mix of machines and humans," he says.

The Multiple Biometric Evaluation 2010 tested facial recognition algorithms from seven vendors and three universities. The tests used nearly 4 million images from three separate sources: a lab dataset, law enforcement and the U.S. Department of State.

Accuracy was measured for three unique situations:

Facial recognition systems typically return a set of possible matches that a human operator then reviews. The most likely match as determined by the system is provided in the first position also known as rank one.

Using the most accurate face recognition algorithm, the chance of identifying the unknown subject at rank one in a database of 1.6 million criminal records is 92%. Obviously, this accuracy rate decreases as the population size increases. In all cases a human adjudication process is necessary to verify that the top-rank hit is indeed the correct individual.

When the most accurate algorithm is used to provide trained examiners with the top 50 ranked candidates, 97% of searches yield the correct identity in a fixed population of 1.6 million subjects. In cases where the top 200 candidates are searched, the correct match is present 97.5% of the time.

Interestingly, it was observed that men are more easily recognized than women and that heavier individuals are more easily recognized than lighter subjects. Also Asian subjects are more easily recognized than Caucasian.

Why systems have had this difficulty is hard to explain. That fact that men were more readily recognized than women could be because women are generally shorter than men. The height of the subject could create non-optimal imaging angles if the camera height is not adjusted.

Test participants: